What ‘Cunningham’s Law’ Really Tells Us About How We Interact Online

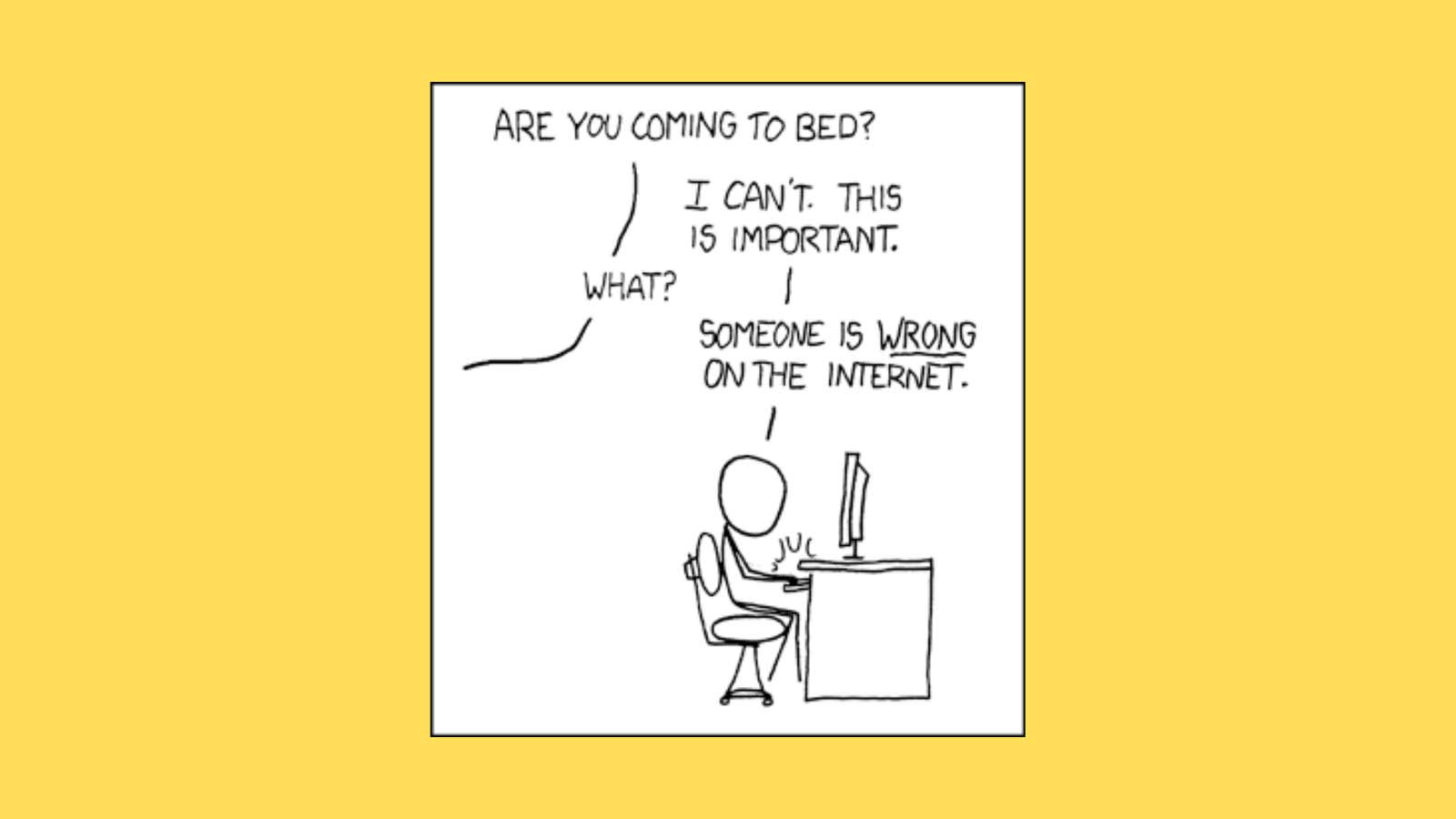

I’m sure you’re familiar with the XKCD “Duty Calls” comic , in which internet users type passionately late into the night because ” someone on the internet is wrong!” The comic illustrates Cunningham’s Law, the derisive axiom that says, “The best way to get the right answer online is not to ask a question, but to post the wrong answer.”

The principle behind Cunningham’s Law isn’t new—there’s even a French saying that translates to “preach lies to find out the truth”—but even though Cunningham’s Law is well established, it’s hardly an effective way to gather information. on the internet – and actually tells us more about how the internet seems to invite us to disagree with everything.

Philosophy of Cunningham’s Law

Publishing lies to get to the truth works (sometimes) because people like to appear smarter than others. But while the dopamine rush and smugness that comes when a stranger feels stupid is a stronger motivator than answering a question honestly, the content of those answers is likely to be far worse. This means that while the number of people deliberately posting incorrect information in search of correct answers is probably small, you can’t really trust hot fixes posted in response to any nasty opinion you encounter online, even if it was sincerely expressed.

Why Cunningham’s Law Doesn’t Work

- It refutes itself. The Cunningham Law is credited to Ward Cunningham , the man who created the first online wiki through former Intel chief executive Stephen McGeady , who worked with Cunningham as early as the 1980s. But Cunningham says he never said it and doesn’t believe it. “I never suggested asking questions by posting wrong answers, ” Cunningham says in the video, “that’s a misquote that disproves itself by spreading around the internet like Cunningham’s law.”

- It’s not a “law”. If the best way to get the right answer on the internet was to post the wrong answer, there wouldn’t be so many lies on the internet.

- It’s more trouble than it’s worth. If you have an actual question, posting a misleading query somewhere on the internet and hoping some jerk will notice is a lot harder than just looking up the answer yourself. And easily verifiable facts are the only way a “law” is even slightly useful. For more complex questions, Cunningham’s law is completely useless.

- Internet proofreaders are almost never real experts. Defendant Cunningham’s motivation is likely to be something like “I’ll show them !” but “putting idiots in their place” is mostly the prerogative of insecure people who have time. People who have experience in a difficult field are much more likely to sigh and shake their heads sadly than they are to correct some random Facebook post. Dealing with anyone who thinks there is something stupid on the internet will take a lifetime and will make no difference, which is why most experts don’t. It remains only to answer the know-it-alls-amateurs and pedants.

- The more complex the question, the more likely it is that the answers will be incorrect. Posting something like “Capitalism is the best economic system” would call out a group of ardent Marxists from their kibbutzim to tell you how wrong you are, but if real economists were involved, their response would be something along the lines of “it depends” or “it’s complicated.”

- What we want to be true vs. true: Crowdsourced echo chambers like Reddit and Twitter are notorious for spreading misinformation. People tend to vote/like/share things they want to be true, not the actual truth, so the appearance of your question being corrected is often more about its popularity than its veracity.

- The Hidden Motivation and the Inconvenient Truth: I’m far from an expert, but I do have a working knowledge of genre screenwriting—I went to school for that and worked professionally for a while. I used to visit screenwriter forums and once honestly answered a user’s question about the possibility of making a living as a screenwriter while living in the Midwest. This was met with a lot of furious messages from both aspiring screenwriters and screenwriting experts telling me that I don’t know what I’m talking about and that I’m a total idiot. It was the opposite of Cunningham’s Law: I know it’s extremely rare for someone to make money as a screenwriter, especially if they’re not in LA or New York, but if you read the forum, you’ll come to the opposite conclusion. Users didn’t want to be told that this probably wouldn’t happen to them. The “experts” said that I was wrong too, because they make money from books and seminars that rely on their grades, believing in the possibility of success in the movie business. Most people with professional experience would agree with me, but they left the forum a long time ago, no doubt after facing the same kind of anger as I did. End result: For anyone reading this forum, according to experts and writers, screenwriting is a viable career.

- Spreading lies. In this article on The Outline , Kevin Donnellan tested Cunningham’s law and spent a week posting unscrupulous facts online in the hope that they would be corrected. He was mostly ignored, but the post he made on the Facebook astronomy group was not. He took a picture of a cosmic volcano on Venus with the caption: “Three-dimensional perspective of Maat Mons on Mercury.” The commentators didn’t respond, “It’s on Venus, you impossible idiot.” Instead, the post was liked and commented on as if it were true. Hours later, someone corrected it, but until then, anyone in the 240,000 group that saw the post believed it and potentially spread it.

- It’s low-key trolling. The motivation of Internet screamers is clearly to prove that they are smarter than you. But what about the motivation of people who post fake questions? It’s a different level of trolling, but it’s still trolling. You should avoid participating in the terrible attitude of people towards each other on the Internet. At the risk of causing controversy in the comment section, we may be better than this.