The Biggest Mistake You Can Make in Any Conversation

Have you ever tried to solve a friend’s problem when he really wanted to speak out and sympathize? Have you ever asked for advice and received only sympathy? Have you ever tried to resolve a dispute while your partner is still racking up new allegations and complaints? In all these cases, the problem is that you did not agree on the scope of the conversation.

This is such a broad problem that a very abstract language is required to analyze it. LessWrong’s essay, Noting Frame Differences , takes time to get used to, and may take several reads to understand. But once he clicks, you have a helpful mental model to help you during an unproductive or frustrating conversation.

How frames work

A frame, as writer LessWrong Raymond puts it, is a way to “see, think and / or communicate.” There are countless frames, but some of the main ones we use in communication are:

- Solution

- Share feelings

- Asserting authority

- Making deals

- Just shoot shit

Each person uses a frame in every interaction. (Even if the frame “fill the silence until the elevator reaches your stop.”) Sometimes all participants in the interaction use the same frame:

- You and the salesperson in the store are simultaneously transacting and collecting courtesies.

- You and your colleagues are complaining about management.

- You are watching the play, so you accept your role as the silent spectator.

The fact that both of you are using the same frame does not mean that the interaction will be enjoyable. Sometimes you both use the same negative frame:

- You are engaged in a screaming fight in which you and your partner express all your grievances.

- You exchange snide remarks with your nemesis.

- You and your partner in the airplane seat have a fight over the armrest.

You understand what the other person is trying to do – you are just trying to do it harder.

How frames don’t match

When the participants in the conversation are held to different frames, it is more difficult for each of them to achieve their goals – be it the goal of “making a deal” or “having fun at a party.” For instance:

- You want to brainstorm for a specific project on a tight budget, but your colleagues want to come up with ambitious ideas for new projects.

- You want to gossip about a friend you really like, but your partner wants to fix what he sees as deep flaws in your friendship.

- You want to hang out with a friend, but he wants to prove that he is more educated than you.

- You want to express an idea, but the internet commentator wants to find fault with your grammar.

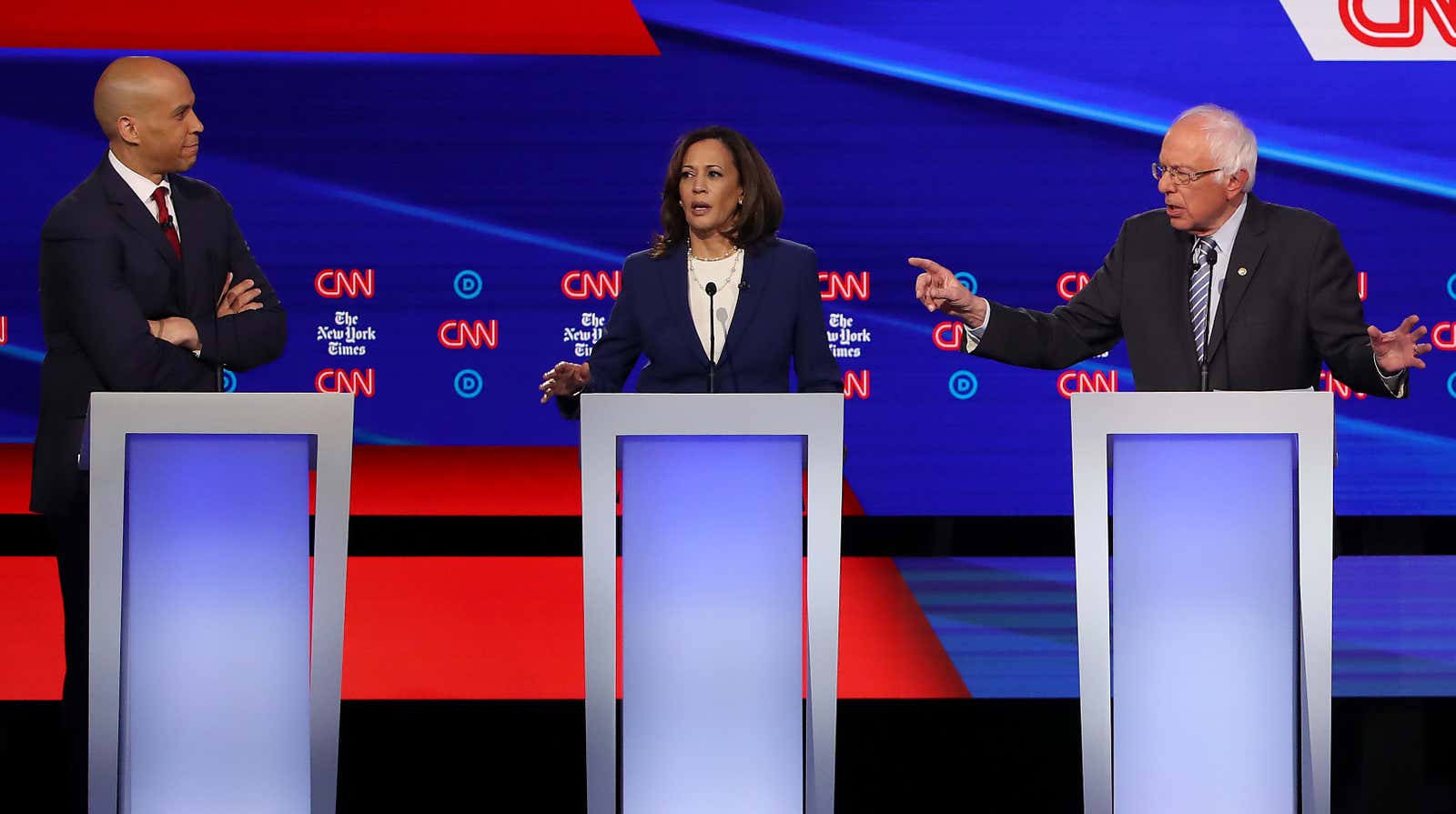

- You want to explain your presidential legislative agenda, but your opponent wants cheap points.

- You want to sit quietly in the theater, but the audience is participating in the comedy performance, and now the actors are trying to drag you onto the stage.

- You want to do anything, anything, like a woman, but a man wants to pester you.

When the parties have different frameworks, it will be difficult for both parties to achieve their conversation goals, although one party may be more successful than the other. A conversation cannot go in a productive direction until everyone falls into the same box.

Raemon lists more examples, which can range from obvious frame differences to subtle – even within the boxes above. Reading them all will help you better understand and recognize differences in footage.

How to solve the frame difference

To get into the same frame, you first need to notice the inconsistency. Neither me nor Raymond have a quick fix for this problem. But pay attention when you or the person you are talking to seems frustrated or wasting time. Pay attention to what you think is a productive conversation, but then none of the results of that conversation will materialize. And look for relationships that seem less and less satisfying to you.

You also need to understand if everyone you are talking to is conscientious about this conversation. Ideally, everyone wants to be in the same frame. Usually you are on the same “team” and you have common goals.

In these cases, when the frames do not match, you can accept and accept their frame, ask them to accept yours, or agree to work in both frames simultaneously or sequentially. (When you’re in a workshop, planning a project, but also gossiping a little, you’re showing two frames at the same time.)

It also works in terms of competition: agreeing to play Fortnite without hacking, or enforcing Robert’s Rules at a city council meeting. This is especially helpful in finding an external ruleset that none of you came up with. If the framework does not match, you can contact this authority.

But sometimes your partner doesn’t care if you fit his image. The entire conversation is an individual exercise in which you happened to be present. (This is fairly common when, say, someone just wants to vent their anger at you, or has inappropriately lashed out at you.) Sometimes you realize that you are someone who doesn’t care about frame matching.

In such bad faith cases, it is often prudent to disconnect, regroup, and consider re-engaging under more clearly defined conditions. Ultimately, you should try to avoid as many unscrupulous frame mismatches as possible, and when you can’t avoid them, catch them every time. Dishonest frames are less effective when explicitly recognized.

Examining frames is a useful way to mentally step back from your interactions, taking stock of what you are accomplishing when you talk to your friends, coworkers, bosses, family, enemies. To understand why you feel like you’re banging your head against a wall. Because nobody is a wall. You are just two people banging their heads against each other. Which, in my experience, is rarely a perfect interaction.