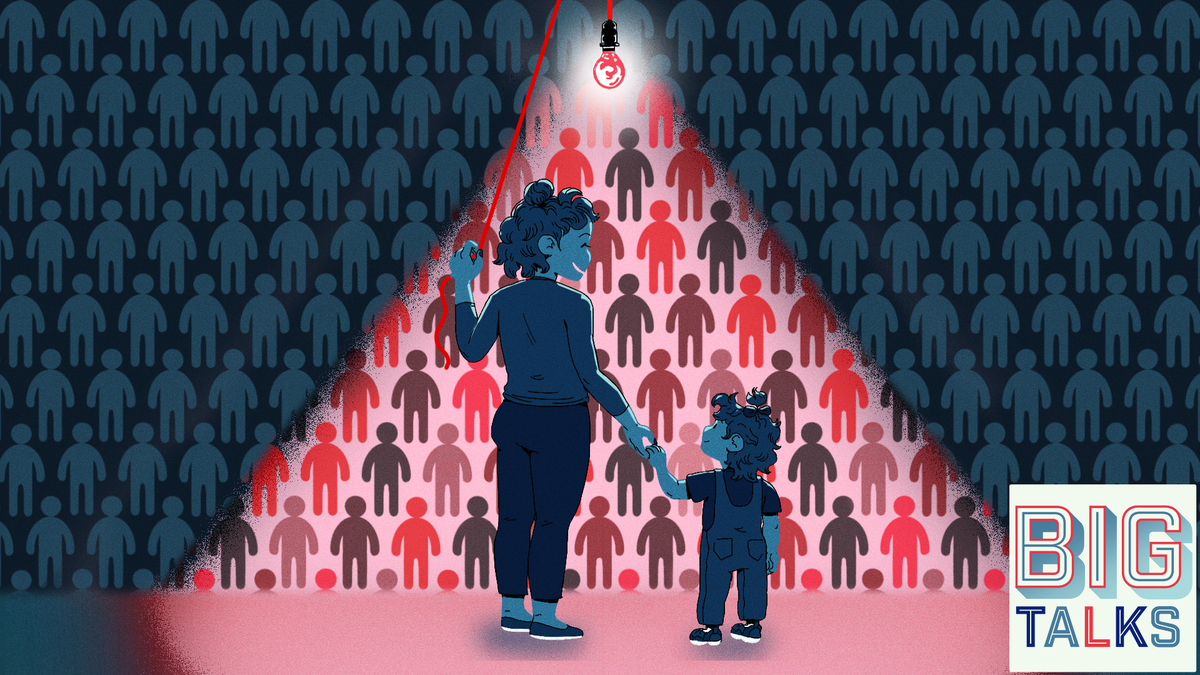

A Guide for Different Ages on How to Talk to Kids About Race

This post is part of our Big Conversations series, a guide to help parents navigate the most important conversations they will have with their children. Read more here .

Like adults, children are not blind to race and do not forget other racial or ethnic differences. If we do not talk to them about race from an early age, they will begin to form their own thoughts, assumptions, and prejudices based on normal cognitive development, the society they grow up in, and other factors that we may not know. be aware of. That’s why it’s important to start talking to them about race when they’re young, and develop those conversations when they get older and can understand more nuances about racial differences, racism, systemic racism, and privilege.

Here’s how to talk to kids about race from around age 3 through adolescence.

Talking to children 3-5 years old about racing

“At around age 3, children begin to notice race and develop their own labels for racial differences,” says Dr. Erin Pahlke, an assistant professor of psychology at Whitman College , whose research focuses on how children and adolescents form their views on race and gender. Around this age, children may spontaneously comment on certain aspects of racial or ethnic differences.

“So they say things like ‘This person has weird hair’… or ‘Why does this person have dirty skin’ or something like that,” Palke says. “It’s important for parents to recognize that it’s developmentally appropriate and that’s what kids do and be prepared for it.”

At such times, parents should, as if nothing had happened, acknowledge the difference and offer simple explanations. You might say, “Oh, he doesn’t have weird hair, it’s just different from ours, but I think it’s great.” You can also explain why people often share similar traits, such as hair or skin color, with family members. What parents should not do at such moments is to quickly shut up the child out of embarrassment or tell him not to say something like that because it is “rude”, which completely stops the conversation. When parents do this, Palke says, you’re not giving them the information they need, and instead of the right information, they’re more likely to come to their own conclusions.

For example, Palke said that she once did a study with a 4-year-old boy, and one of the tasks of the study was to sort images into different categories. He sorted pictures of people who appeared black into one pile, and pictures of people who appeared white into another. When Palcke asked him how he would label the people in each stack, he said that the stack of photographs of blacks was “smoky” and that of whites was “not smoky.” When Palke asked him what he meant, he told her: “My parents told me that if you smoke, your lungs turn black. So all these people smoke here, and none of these people smoke.”

“And it’s not surprising that he had really negative racial views, because his parents taught him very well that smoking is bad,” Pahlke says. “And when I later talked about it with his mom, she was horrified and said: “You know, I didn’t even realize that he noticed skin color or racial differences.”

Palke also adds that it’s important to have a collection of books and toys that reflect racial diversity (and you should do a personal audit from time to time to make sure these things really represent the diversity of the world), but just having them isn’t everything. replace actually talk about the race. (If you want to start building a diverse book collection for your child, she personally recommends Us in Flowers by Karen Katz .)

Check out these anti-racist books for kids:

- anti racist child

- Hidden Figures: The True Story of Four Black Women and the Space Race

- Children’s book about racism

- The Antiracist Child: A Book on Identity, Justice, and Activism

- Child Activists: True Childhood Stories from Champions of Change

Talking to children 6-8 years old about racing

By the time children enter elementary school, Palke says, they begin to associate positive traits with their racial group and negative traits with other racial groups.

“And there are several reasons why it has to do with cognitive development, and there are also several reasons why it has to do with the society we live in,” she says. “So at the end of the day, for example, white kids often choose white dolls and white friends, and activities that white kids participate in, and things like that. Therefore, parents want to pay close attention to behaviors that may indicate bias.”

Parents should model having their own diverse groups of friends and look for activities or other forms of community involvement that include people from other racial or ethnic backgrounds. It is also important at this age to start teaching children about the history of race relations, especially for white families who lag behind families of color in these discussions.

“One of the things that happens when you talk to, for example, black kids versus white kids, is that black kids at a younger age often have a more developed understanding of racism, and part of that is because they parents report talking to their children. children about racism,” says Palke. “So, black families — and, increasingly, Hispanic and Asian families, research shows — teach their children about the history of race relations in the United States and the world from an early age, and begin to prepare their children for the racism with which they may collide. Likewise, white families should tell their children about this story.”

Talking to teenagers about race

Although Palcke says there is a move away from the “colorblind” ideology in the US ( as we said earlier, children are not colorblind to other races), by the time children move into late primary or middle school, they begin to internalize the idea of that race and ethnicity are taboo topics.

“Maybe it’s not something they directly talk about,” she says, “but it’s what they think about, and their attitude continues to evolve.”

Palke says research shows that by age 10, most children can define racism and develop ideas about the causes of racism. That’s why it’s important at this age to start talking not only about the individual types of racism that one person can face, but also about the systemic factors that persist today. For example, they may notice that we have never had a Hispanic President in the United States, or they may see a news report about the top executives of a large company and realize that the group is predominantly white male.

“Children are trying to come up with an explanation for why this might be so,” Palke says. “And if you don’t explain to them the history of racism and sexism in this country, they sometimes assume that it’s just that these groups of people either don’t want to do the job, or they’re too lazy, or they don’t work hard or they can’t.”

Around this age, parents may begin to explain and point out the systemic factors that create inequality and how white privilege still exists . (We have a complete guide to talking to white kids about their privilege here .) Talking like this can be motivational as you as a family look for ways to get involved in your own community to help change the system.

“Currently, there are some studies that show that people who understand what white privilege is, if they believe in the concept of white privilege, they are more likely to strive for social justice,” Palcke says.

Talking to teenagers about race

By the end of high school and high school, teens should have a fairly clear understanding of the history of U.S. race relations and the systemic issues that still exist, and they should be able to begin identifying racial inequalities on their own. For example, in some school districts, they may notice disparities in issues such as access to honors classes, and you can talk to them about what can be done about it or how to make a positive change.

“Young people feel better when they feel they can make a difference,” Palcke says. “If you have high school students who [admit] problems with systemic or institutional racism, say, ‘OK, what can you do to help change?’ It’s positive for them and also positive for the community because high schoolers can be a strong group.”