This Vintage Martha Stewart Recipe Makes Candied Fruit Easy to Make.

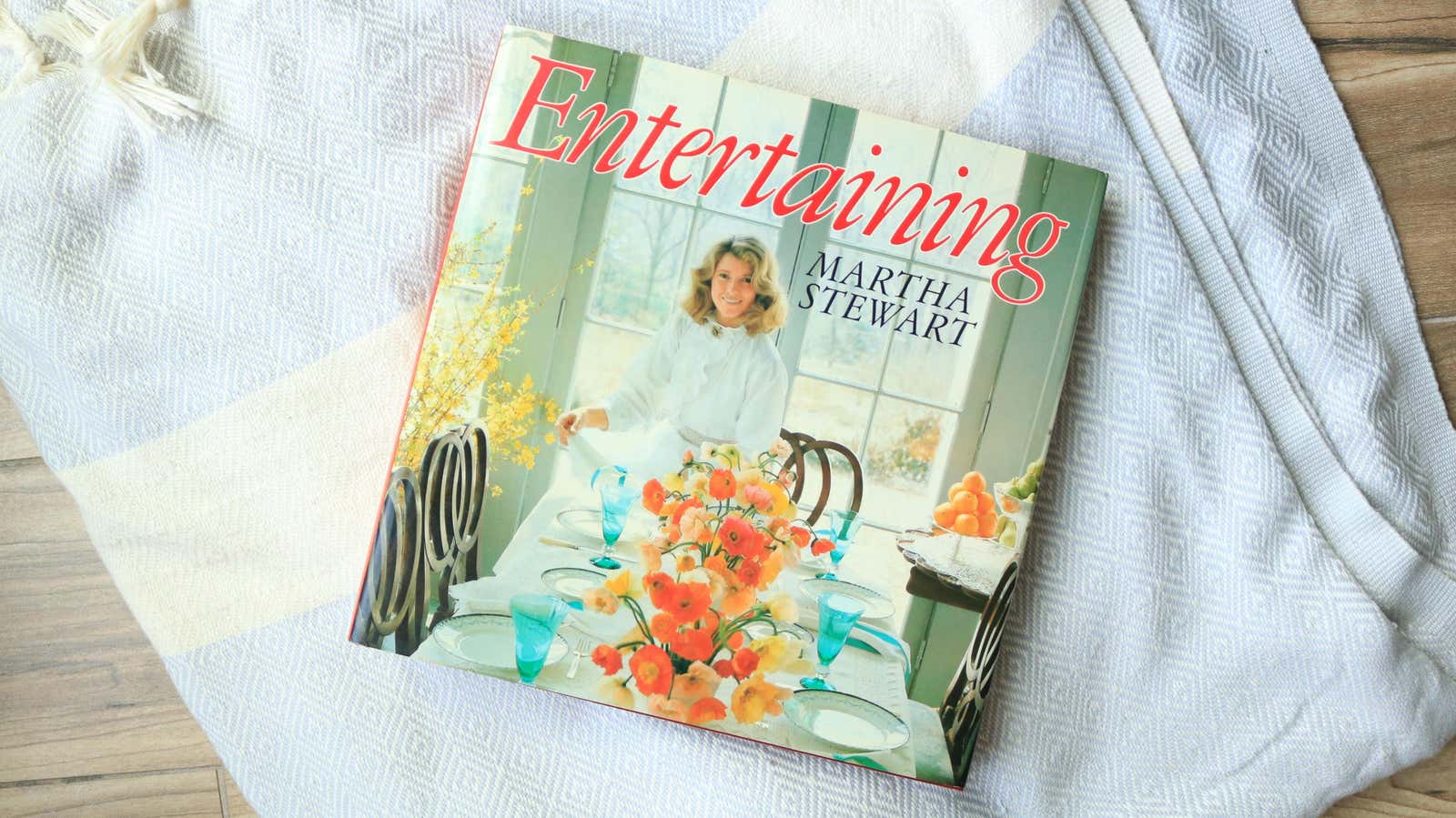

I love hosting dinner parties, but I hate host anxiety. To combat this, I’m always looking for beautiful, impressive recipes that are secretly simple. Ina Garten and Martha Stewart are two chefs and undeniably great dinner party planners who have mastered recipes like this (technically I haven’t been to their dinner parties yet but give me time) and since my mom recently dug up her copy of ” Entertaining ” (1982), Martha’s vintage book on how to throw the perfect party, I turned to her for advice and found Martha’s simple tip on how to make a tempting fruit plate: pour icing over fruit.

What is Glazed Fruit?

Glazed fruits are essentially raw fruits that have been coated with sugar icing, which gives them a gorgeous reflective sheen. Although the term is French, this technique is used to prepare the equivalent Chinese street food called Tanghulu and is probably practiced in many cultural cuisines. Applying this candied technique to fresh, in-season fruit produces elegant results, and it looks especially good on a cheese board. An added benefit: The sweetness of icing sugar can help out-of-season fruit taste.

To glaze fruit, prepare melted sugar syrup and carefully dip fruit in it just long enough to coat. End. A thin layer of sugar cools down within a few minutes and, shining, clings to the surface of the fruit. Pretty simple.

How does Martha do it?

Martha’s recipe uses strawberries and green grapes, but I tried it with fresh cherries because I have a lot of them. Since you will be dipping the fruit in melted sugar that is over 250 degrees Fahrenheit, fruits with spectacular stems are highly recommended. Cherries, bunches of grapes and strawberries are easy to hold and dunk. Everything that does not have a stem can also be strung on a skewer and dip. Whatever fruit you prefer, make sure to get most of the sugar out of it, as chewing on a big wad of candy is not fun.

The first step is to prepare the fruit. Wash and dry it and make sure it is at room temperature. The goal is to ensure that the sugar adheres smoothly to the skin of the fruit. Any moisture (including condensation from cold fruit) will quickly evaporate when fruit is immersed in very hot sugar, and can lead to potentially dangerous steam splatter, strange cold spots that lower the temperature of the syrup, or (at best) small bubbles, which slightly spoil the gloss of the glaze. Just start with room temperature fruit, okay?

When the fruit is dry and ready, make the hot sugar syrup. Use a small, deep saucepan and at least one cup of sugar with a couple of tablespoons of water. In Martha’s recipe, she uses two cups of sugar to top several bunches of grapes and a pint of strawberries. You won’t use all of the syrup, but you want a puddle deep enough to dip the fruit in quickly and easily. I don’t know if I told you this, but this sugar is hot as hell, and you need to act quickly so as not to boil the fruit.

Cook the mixture over medium heat until the steam stops coming out (because all the water has evaporated) and the bubbles start to get smaller and bigger. Use a candy thermometer to check the temperature if you’re unsure. The recipe suggests that you drop the fruit once the syrup reaches 265 degrees Fahrenheit, which in candy terms is called the “hard ball stage”. Dip each fruit long enough to coat the outside and place on an oiled baking sheet to cool. That’s all for Martha’s recipe, but I’ve made some adjustments.

I didn’t like how the candied surface of my fruit turned out. The hard ball stage is best for sticky, chewy candies like caramel. I love caramel, but this is not the same. When you bite into a fruit, sugar immediately sticks to all your teeth. The cherries also stuck to each other when I tried to cover them with plates, which would have been terrible in a dinner party situation. Instead, I’ve found that cooking the sugar to the “soft crackle-hard crackle” stage works better for my cherries. The fine sugar coating crumbled as I bit into it, creating a nice combination of textures with soft, ripe fruit. The sugar was crunchy, not chewy, and dissolved in the mouth. The coating process has also improved; the sugar in hard crack is not as sticky unless it gets wet. To prevent this, cover the fruit within an hour or two after you plan to use it and place it in an airtight container.

The final change I suggest is to refrigerate the fruit on an oiled dryer after dipping. Despite my best efforts, some sugar still accumulated at the bottom of each cherry when placed on a parchment-lined baking sheet. A drying rack would allow me to quickly shake off excess sugar, making the coating as thin and smooth as possible.

With just a few tweaks, this cooking technique is dazzling: a tempting way to present the abundance of summer fruit. If the idea of completely covering the fruit in candy makes your teeth hurt, you can simply drizzle syrup over the fruit instead. Just spread the fruits on parchment paper and drip sugar syrup on them. The result will be sparkling pieces that appear freshly picked on a dewy morning.