We’re Not Ready for Monkeypox

Monkeypox is already here, and it’s spreading. The couple dozen cases in several countries that we told you about last month have now surpassed 1,000 cases worldwide, 35 of which are in the United States. But there are almost certainly more cases in the US than statistics suggest, and there is reason to suspect that we have already messed up the response to the epidemic in ways that may seem uncomfortably familiar.

We don’t test enough

In the first few months of the COVID pandemic, when we had the ability to contain the virus if only we could find all the cases and their contacts, testing was grossly inadequate. Many people who had the virus were never tested for it, and people who wanted to get tested weren’t always able to get it. We knew at first that the virus was spreading silently because there were cases in the US that were not linked to each other. The genetics of the various foci of the outbreak may show that the virus spread undetected for some time.

Here’s what’s starting to happen here: there are small clusters of monkeypox cases that are genetically distinct enough that we know there must be far more than the 35 reported cases in the US. So many cases should go unnoticed.

One reason for undertesting is that people with monkeypox may not realize they have it. Typically, monkeypox foci are widely distributed throughout the body. In an ongoing outbreak, sometimes a person may have lesions in only one part of the body and may even have a single lesion. When this happens, you don’t think, “Oh my God, that must be monkeypox,” you think, “Ha, I wonder what that spot is.” And maybe you will see a doctor, maybe not.

Doctors also don’t necessarily look for monkeypox and may not recognize it at first. It is not a common disease in the US (or many other areas where it is), and the symptoms of this outbreak do not always follow textbook sequence. You usually expect a fever first and then a rash; but in some known cases the rash appeared before the fever. Some people have lesions only in the anal or genital area, which can be confusingly similar to STIs such as herpes or syphilis. (Molecular microbiologist Joseph Osmundson compiled a fact sheet that includes photographs of anal and genital monkeypox lesions .)

So the first hurdle in testing is that not enough tests are done in the first place. Monkeypox testing involves collecting secretions or scabs from lesions and sending them to one of several specialized laboratories. Former FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb tweeted that the current bottleneck is the lack of sampling.

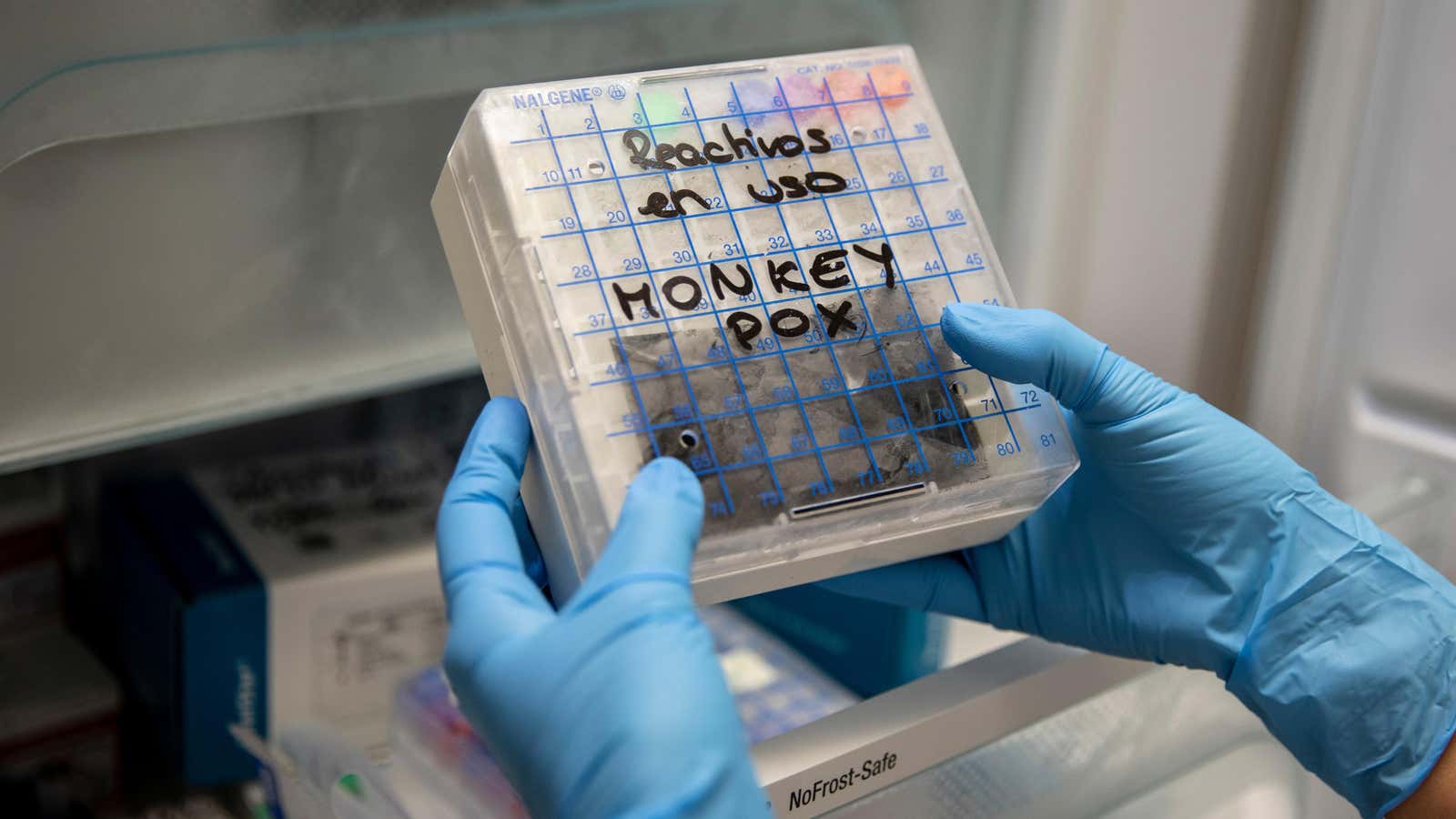

But if awareness improves, we may soon face a bigger problem: laboratory testing capacity . There is currently a network of 74 laboratories that can test for orthopoxviruses and they can process approximately 7,000 tests per week. Monkeypox is the only orthopoxvirus of current concern because smallpox has been eradicated and other viruses in this family, such as vaccinia, are rare. If the sample tests positive for orthopoxvirus, the CDC will do more testing to confirm it’s monkeypox.

People with monkeypox (or orthopoxvirus, which is suspected to be monkeypox) are supposed to be isolated for 21 days, while health authorities will trace contacts and offer vaccines to the infected person and their close contacts in the meantime. There are also antiviral drugs that may be helpful. But the vaccine brings another problem.

We have a vaccine, but we don’t know how well it works.

The good news about the vaccine is that we already have it. More than one, actually: smallpox vaccination has been around for hundreds of years , and several modern vaccines are still available. (In 1980, smallpox was declared world-wide eradicated, the only human virus to be so honored.) Humans can sometimes have fatal reactions to some of the older smallpox vaccines, so vaccines that use live virus do not are considered. for monkeypox.

In the US, there is one vaccine licensed for use against monkeypox. It is known as MVA (from Modified Vaccinia Ankara) and its trademark here is Jynneos. It does not reproduce in humans, but still elicits an immune response against smallpox. According to a 1988 study, vaccination is 85% effective against monkeypox transmission, but this was a small study and we do not know if such effectiveness can be expected from the current vaccine and the current strain of monkeypox.

We also do not know if this is enough for us. The US Strategic National Stockpile says they have 36,000 doses with 36,000 more on order. The vaccine company understandably also has many recent orders from other countries, and they plan to ship small batches to different countries so everyone can quickly start vaccination.

This vaccine is not enough to start vaccinating everyone, so the current strategy is “ring vaccination”, in which the vaccine is offered to people who have been in close contact with a person who is known to have monkeypox. (The monkeypox vaccine can also be given to a person with monkeypox, as it can reduce the severity of the disease if caught early enough.) But contact tracing isn’t perfect, and in many recent cases people didn’t have names or contact information. to all their close contacts. Another possible strategy could be to offer the vaccine to everyone in the high-risk group, which currently includes men who have sex with men. So far, this strategy has only been tested in Canada.

People already misunderstand how it’s transmitted

Many of the recent cases have been reported in men who have sex with men. This has led some people to assume that it is sexually transmitted, such as HIV or other STIs; I’ve already seen social media posts from people misunderstanding this and saying that you can only get monkeypox from having sex with someone who has it.

Knowing that the virus is sexually transmitted is useful to know if sexual transmission is the main way the virus is spread, as is the case with HIV. But we do know that monkeypox can be spread by close contact of any kind, including contact with an infected person’s lesions or respiratory droplets (for example, when coughing or sneezing), and perhaps even aerosols.

And on that note: The CDC briefly published a recommendation that travelers should wear masks to avoid contracting monkeypox, and then rescinded the recommendation, saying it “caused confusion.” Can monkeypox be airborne? Maybe ! But if you’re afraid of contracting the virus while traveling, you should still wear a mask. We already know that masks (especially well-fitting N95-style masks) are effective in protecting us from COVID, and COVID cases are on the rise again – not that they’ll ever go away. So yes, wear a mask. But also watch for monkeypox symptoms and don’t be afraid to ask about a test or vaccine if you suspect you have monkeypox or may have been infected.