I Baked Sourdough Bread From a Viral Tweet and It Didn’t Kill Me

Baking sourdough bread has become a cliché of negligible privilege in an era of social exclusion. This is a time-consuming attempt to stay at home, which for some reason every blogger decided to tell about in my news feed, and I made fun of it. But after baking a loaf solely on the advice of a viral tweet and his tweet, I realize that maybe these bakers are doing something right. After all, they are the ones enjoying the freshly baked bread, and the process was not as difficult as I thought.

If you’ve visited a grocery store in any big city, you probably discovered the missing products as triggered our instincts to survive in the day of judgment – no toilet paper, no soap, no, curiously, no yeast. Last month, a tweet thread by biologist and self-proclaimed Viking Sudip Agarwal went viral, poking fun at this predicament: “YEAST NEEDS NEVER,” he shouted on Twitter. If you have dried fruit, flour (which is also impossible to find in many supermarkets these days, but let’s forget that for the purposes of this story, since you won’t bake bread without it anyway) and water, you have everything you need. yeast you need.

As a biologist at renowned synthetic biology company Ginkgo Bioworks, Agarwala had the right to make such claims. And I am a lover of light kitchen projects. So I thought, if there really isn’t any packaged yeast left, can I create a delicious loaf of sourdough bread that I’ve grown based on just one tweet?

Before we start, I must tell you that I am not a complete beginner when it comes to kitchen experiments. I have had a long interest in nutritional science and have written about fermentation , gluten, and molecular gastronomy . Sometimes I experiment with pickling or fancy chemicals in my own kitchen. But growing and growing yeast is something I’ve never done before – in fact, I’ve only baked yeast three times in my life, always with packaged active dry foods, and in one of those cases the bread was so bad that I had to throw it away.

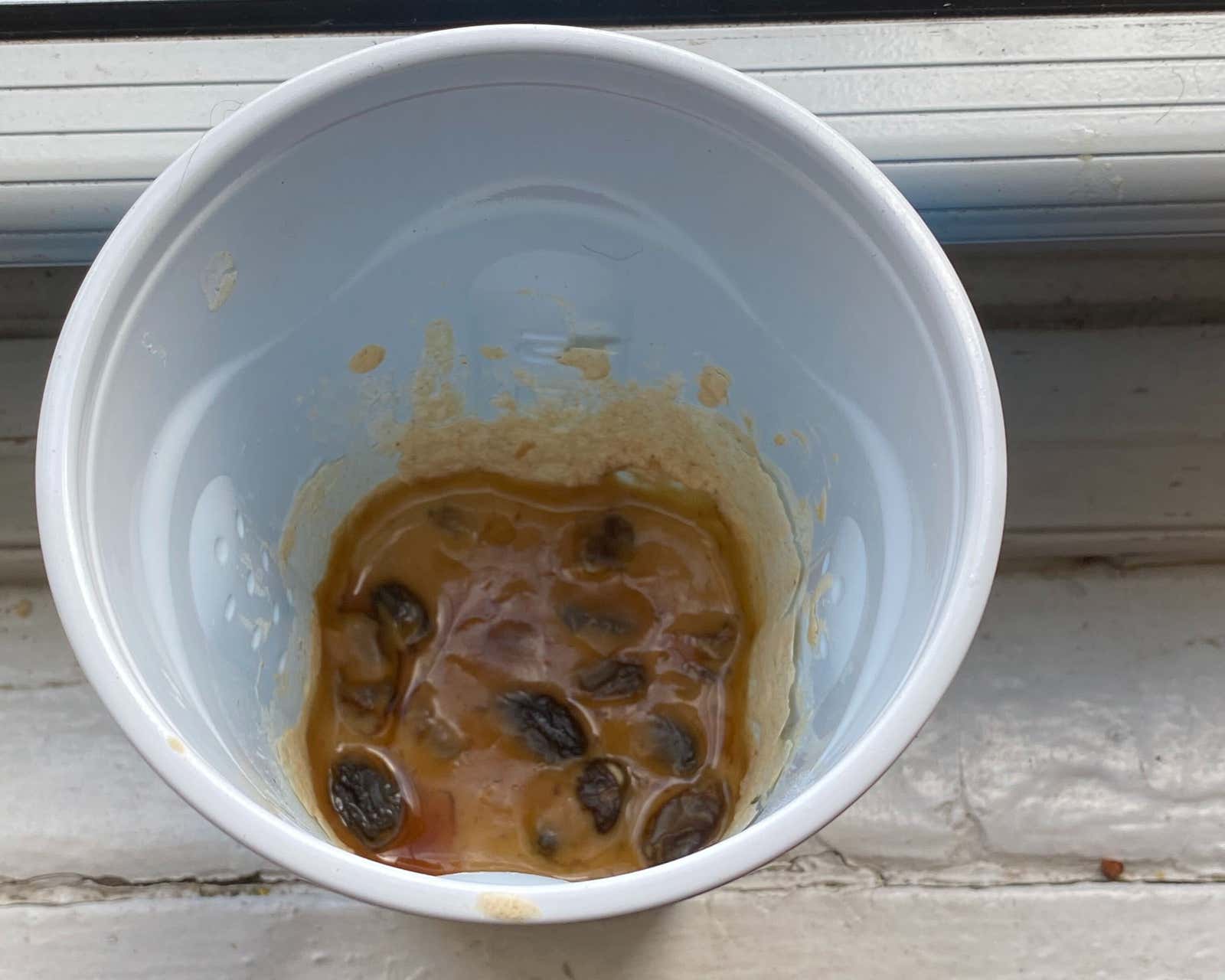

I found a container – a Solo bowl that showed how serious I was about to take this business – and set to work following Agarwal’s instructions. I mixed the old raisins I found in the cupboard with two tablespoons of water and mixed. The water did not turn cloudy as expected, but I moved on. I added the same amount of flour (by weight) as I had water, mixed and put the cup in the sun to keep it warm. I figured the process would be completed in a day, and by the end of the week I would be baking.

Why did I choose raisins? “There is yeast in wheat, so you can mix it with water, and in a week you will have something. But I’m not a patient person, Agarwala told me. “The nice thing about adding raisins is that you add a source of sugar to the starter and add some yeast to it.” He said the system grew him into a usable starter in 24 to 48 hours.

It took me several weeks. But we will come back to this.

It’s true that yeast is everywhere – in fact, it is a vast group of single-celled organisms in the fungal kingdom. Our relationship with the yeast fermentation process likely began with brewing: wild yeast cells from the environment ate carbohydrates in the cereal infusion, releasing carbon dioxide to form bubbles and alcohol that inhibit the growth of more dangerous microorganisms. At some point, ancient bakers probably noticed that their dough was bubbling due to the yeast eating up the sugar in the flour, causing the dough to rise and change the texture of the bread.

Today we have tamed yeast to the point where you can buy it in stores and in most cases expect it to do whatever you want it to do within a few hours, using its fermenting properties to sour bread. The emitted carbon dioxide causes bubbles to form in the dough, which are trapped by a grid of gluten proteins in the flour. Baking the dough blocks the bubbles in place and also induces browning or a Maillard reaction , which gives the bread a flavorful outer crust. You can still get these effects from wild yeast – it just takes longer and you have to tame it yourself.

A day after the first mixing of raisins, flour and water, I looked into the Solo cup – there was a single bubble. Proud of my successes, I took some pasta made from flour, water and raisins, mixed more with flour and water, and waited. After two days, the mixture formed a brown liquid with a crust on top, but no new bubbles. I figured it out as doing something wrong. (Chances are the raisins were washed out at some point and I didn’t have the patience to let the yeast from elsewhere seep into the paste.)

Deciding to raise my own yeast monster, I started all over again, now with a crust of bread instead of raisins. I fed the yeast beast daily, discarding all but a portion of the pasta and adding equal amounts of flour and water. I learned from A.A. Newton that you can microwave your starter with a bowl of hot water to create the nurturing environment you need to thrive. The Solo cup smelled a little of vomit, but a quick Google search told me that vomiting isn’t such a bad smell in the first few days after souring. In addition, every night a crust formed on its surface, which, as I eventually found out, was because I left it open. And after a few days my starter culture started to grow well – it hadn’t foamed yet, but at least there were really visible bubbles.

As Easter approached, I continued, knowing that my new hobby was the exact opposite of the holiday, during which I was forbidden to eat leavened bread for eight days. I was hoping to kick up the yeast over the course of the party, and when it’s over, I’ll have a large and active snack to bake a loaf the night the party ends. But then disaster struck: my lovely snack stopped bubbling.

As Seamus Blackley, the creator of XBox and also a baker, once tweeted , leaven is a kind of “brutal microscopic eugenics program.” As the lord of leaven, your job is to create an environment in which yeast cells defeat all their tiny competitors. By throwing away some of the yeast, mixing it with flour and water, letting it stand, discarding some, stirring in the flour, letting it sit, etc., you increase the amount of yeast in the mixture each time. Meanwhile, another friendly microorganism – a bacterium called lactobacilli – produces lactic acid during its own fermentation process, which ultimately gives the starter its characteristic flavor. You must continue to maintain a suitable environment so the microorganisms can do what you want them to.

It is not clear what happened to my starter. I thought maybe I killed him by cooking in the microwave where I kept the yeast, which made the sourdough too hot. Agarwala theorized that the temperature didn’t kill him, but the environment may have caused the yeast to eat all the sugar and instead resort to consuming the by-product of alcohol, slowing down its release.

Regardless, I didn’t give up easily. While washing brown rice before cooking it, I noticed that the drain was cloudy. Ha, I thought, I just need to pour some of this into the bubble-free sourdough. In two days my starter was regenerating. Every morning I woke up with a crumbly pasta that looked exactly like the sourdough sourdoughs I saw in friends’ houses or on the Internet. It’s finally time to bake the bread.

All this time I have tried my best to make the process as unscientific as possible. Sure, you can treat bread like a science, but I was just trying to think like an average person who wanted to bake based on a viral tweet. So, as far as the bread recipe is concerned, I once again blindly believed Agarwala – this time having received the indicated advice over the phone – by asking him to suggest the recipe. I then proceeded to the baking process, which lasted three days.

First, I mixed 20 grams of starter culture with 150 grams of water and 200 grams of a flour mixture that consisted of three parts all-purpose wheat and one part whole wheat. I allowed the creature to sit in his now permanent microwave at home overnight. The next morning I mixed another 600 grams of this flour mixture with 400 grams of water and left for half an hour. This is the autolysis stage ; the pause allows the enzymes in the flour to break down proteins so that the gluten protein network can form more easily and convert some of the starch in the flour into sugar for a yeast feast. Then I mixed the gremlin in the microwave, added 15 grams of salt (which I learned to taste and strengthen the gluten protein network), gently knead the sticky mass every few hours, and put the dough in the refrigerator overnight to really let the flavor develop.

After a sleepless night of baking, I turned the oven on as hot as possible, put a cast iron skillet on, and then put a smaller skillet filled with ice cubes underneath it. The ice generates steam, which creates a truly humid oven environment. This slows down the development of the crust and allows the bread to rise even more – by the way, that’s why people bake in Dutch ovens, but I don’t have a Dutch oven. I then sliced the top of the bread with a knife, put it on a floured piece of parchment paper and in an overhead pan, lowered the oven to 450 degrees F and baked for 20 minutes. After that, I took out the smaller skillet, let the bread bake for another 20 minutes, took it out of the oven and let it cool for an hour.

How was it? Guys, it wasn’t perfect, but it tasted pretty darn good. The bread definitely had a crust, it came up and was sour, like a loaf you can buy at a famous San Francisco bakery. Obviously something went wrong – the crust was not as hard as it could have been, I’m sure it could have risen more and I had a blowout – basically, the gas could not escape through the slots in the top of the loaf, so that he just flew out of the way. Perhaps my cuts were not deep enough or there was some other heating problem. But I don’t care: I did it and now I have a loaf of bread that I really like.

Through this case, I learned a few things: first, sourdough bread is a very scientific approach; mixing chemistry and biology is a huge experiment with many variables that meticulous bakers must control in order to make the perfect bread. Secondly, I learned that sourdough bread is a chaotic monster that, it would seem, is impossible to control, where something happens just like that, and you fly past your pants, and in a Google search you cross your fingers, hoping that you’ve spent a few pounds of flour on this thing. there will be no disaster. Everything goes wrong and you just keep going.

But most importantly, I learned that yes, if the world ran out of packaged yeast, I could make a raw loaf of bread using the knowledge I gleaned from the viral tweet. It will probably still take a long time, but it won’t be as difficult as I thought.