Everything You Think About Toxic Shock Syndrome Is Probably Wrong.

I found out a couple of years ago that some women insert makeup sponges into their vagina, all the way down to the cervix, to have sex without a mess. After googling and consulting with the women who did it, I decided to give it a try. It was a revelation – all of a sudden oral sex and clean bedding became possible during my period. In July 2017, I wrote a short post on Lifehacker recommending this method without consulting a scientist or gynecologist.

Big mistake. This is terrible, irresponsible advice, many wrote in the comments. Dangerous, stupid, untested, unsafe. Fall asleep with one of them within you and toxic shock syndrome follows. “What if the sponge gets stuck there? What if it causes septic shock or internal urticaria? “You might as well tell people to take extra drinking straws with them when they are at the gas station because they can be used as catheters,” one commentator chuckled . The maintainer described the use of hacking as “a hazard to work ” and not the method she would recommend in her personal life. Several commentators were horrified that we published this advice without the involvement of a gynecologist.

So, I tried to fix this error. I was pleasantly surprised when the physician I consulted did not seem particularly bothered by the myriad horrors described in the comments, although due to their lack of strings and impressive squeeze ability, she did agree with the emergency doctor (and Lifehacker commentator) that the sponges for makeup more often than tampons get stuck in the vagina. I have updated my story with the advice of a doctor. I also learned an important lesson about consulting professionals and including disclaimers before proposing any biohack.

But then Dr. Jen Gunther, an obstetrician- gynecologist known for his vaginal reality tests, wrote a blog post in which she called the makeup sponge “a potentially deadly gimmick .” (“Incredible women will surely ruin their vaginas and possibly die,” one commenter agreed .) The infamous tampon called Rely was found to be associated with an outbreak of toxic shock syndrome in the early 1980s. The Rely tampon was made from, among other things, polyester foam, such as polyurethane, like many makeup sponges.

Then I realized: I don’t know shit about TSS. Of course, I remembered the vague advice I heard when I was 13, not to leave the tampon too long to avoid the disease, the name of which contains three of the worst words in English ( Toxic! Shock! Syndrome! ). I knew that TSS was rare, but I didn’t quite understand what caused it. Regarding my technique for using the makeup sponge, I thought that since I don’t keep sponges in my vagina for long, I probably won’t die if I used them “for other purposes.” But now I wasn’t so sure. I decided to investigate – for real this time.

More than a year later, I emerged from the complex underworld of toxic shock science with much more than I expected, including a lecture by an older man on the “art of making love,” the potential sex benefits associated with TSS. at the beginning and often – multiple accusations of collusion and a history of a bitter rivalry between two outstanding microbiologists, which lasted for decades. I also found out that whatever you think about tampons, menstrual sex, and toxic shock syndrome is probably wrong.

What are we talking about when we talk about STS

Toxic shock was first discovered in 1978 at a hospital in the Denver area by Dr. James Todd after seven patients, ages 8 to 17, fell ill with the same symptoms . Three of these patients were menstruating girls. Each of the patients had a combination of similar symptoms: fever, confusion, shock, diarrhea, headache, and rash. At least one of the patients was diagnosed with scarlet fever, but eventually Todd discovered that it was something new. Because it was caused by toxins that caused circulatory shock in his victims, Todd named this previously undiagnosed condition “toxic shock syndrome.”

Three years later, scientists discovered that the disease was caused by TSST-1 toxin. This toxin is produced by the bacteria Staphylococcus aureus , which can cause anything from acne to food poisoning (or nothing at all – many people have it in their bodies without any side effects). When TSST-1 toxin penetrates the vaginal lining and into the bloodstream, it can lead to low blood pressure, organ failure, and even death. From October 1979 to May 1980, 55 cases of TSS were reported to the CDC. the cases affected women, and the vast majority of these women had their periods when symptoms appeared.

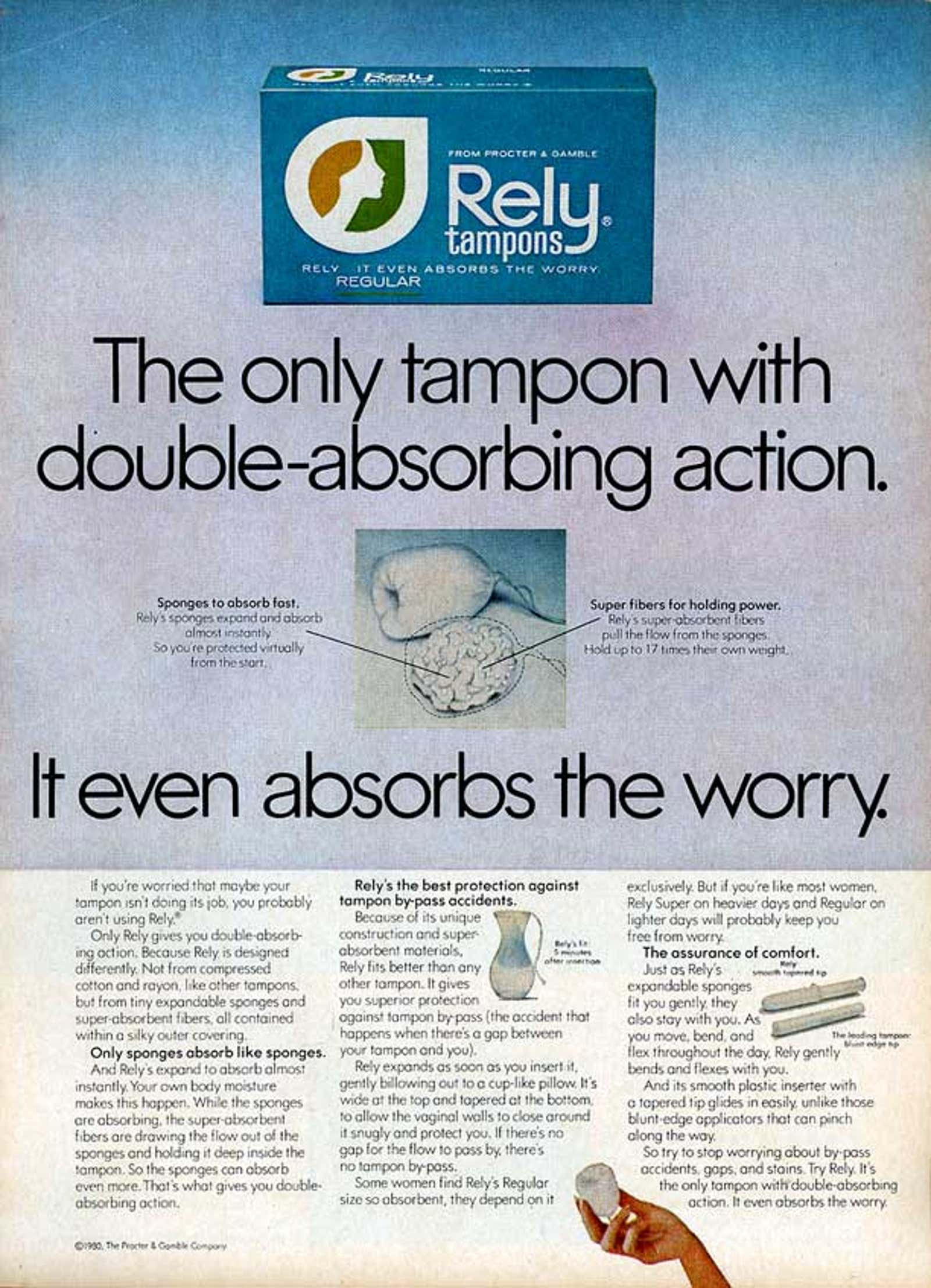

Several studies in the following years have established a link between tampon use and TSS. A far more common incidence of TSS was among women who used Procter & Gamble’s Rely superabsorbent tampon, which was first tested on the market in 1974 and gradually rolled out across the country. Rely was a teabag-shaped tampon that could expand to three times its original volume and absorb liquid nearly 20 times its own weight – “It even absorbs anxiety,” read the marketing campaign. It was made from cubes of polyester foam and chunks of a gelling agent called carboxymethyl cellulose, both of which make the swab superabsorbent; According to The Atlantic’s tampon history , some women only wore one Rely tampon at a time, eventually pulling a giant mushroom object out of their vagina.

The prevalence of TSS peaked in 1980, when 812 menstrual cases were reported , and the incidence of TSS was about 10 per 100,000 among women of menstrual age. The CDC concluded from a survey of select patients that Rely was the most commonly used tampon. After the CDC released a report in September 1980 linking the disease to the tampon brand, Rely was taken off the market. In subsequent years, tampon companies were required to place TSS warnings on their product packaging, and by 1990 all tampons were made from cotton or rayon .

The current TSS is about 1 in 100,000. In 2017, according to the CDC , only 24 people in the United States contracted TSS associated with Staphylococcus aureus (there is also TSS caused by streptococcus, caused by another bacteria). Ask a modern woman what causes this bogeyman disease, and you will hear a lot. Friends of mine from Facebook and colleagues at work had interesting theories: “bacteria trapped in the vagina with an object”, “something about getting wet and then drying a tampon”, “chemicals in the tampons are absorbed by the sensitive tissue of the vagina” or even “Not absorbed.” exists. “But most of their theories about what causes TSS were the ‘tampon left on too long’ version.

Not certainly in that way.

What causes TSS?

Even during its peak in the early 1980s, toxic shock syndrome was a rare condition because the correct combination must be identified in a woman to develop it. At least 80 percent of the female population becomes immune to TSS by adolescence, no matter what their tampons are made of, because they have antibodies that recognize and can inactivate the toxin.

One leading microbiologist, Dr. Patrick Schlivert, professor of microbiology and immunology at the University of Iowa, explained it to me this way: Of women who don’t have antibodies, only 5 percent have a toxic S. yaureus strain in their vagina. There must then be enough S. aureus to develop TSST-1 toxin — high blood pH exponentially increases S. aureus , which is likely the reason TSS is associated with menstruation. In only two-thirds of these cases, when there is enough S. aureus to produce TSST-1, the toxin will be able to penetrate the woman’s vaginal mucosa and enter the bloodstream – and only one-tenth of TSST-1 will be transported. In addition, while American women of Northern European descent appear to be particularly susceptible, there are far fewer reports in the United States of African American, Hispanic, or Asian women contracting it. Considering all of these factors – and the frequency with which tampons are used – the maximum frequency of menstrual TSS could only be 10 out of 100,000 in the United States.

Because TSS is so rare, it is difficult to obtain extensive data on it. But a few of the top microbiologists who have studied toxic shock syndrome for years do have a pretty good idea of what causes TSS, although they don’t seem to agree. After the Rely super absorbent tampons were discontinued, scientists conducted numerous studies to determine the underlying causes of the disease. Many studies have tried to explain why a Rely tampon has been associated with so many cases of TSS. Was it the chemistry of the tampon? Was it because Rely’s outer coating, known as Pluronic L92, increased the production of toxins? Or was it the high absorbency of the tampon that allowed it to swell and grow, and trapped oxygen in the vagina, causing bacteria to produce toxins?

Team Polyester vs Team Oxygen

Dr. Philip Tierno, professor of microbiology and pathology at New York University School of Medicine, insists that tampon material is essential when it comes to producing toxins. Tierno has testified against tampon manufacturers in toxic shock lawsuits and is one of the most recognizable names in the TSS world. Tierno’s influence on pad journalism is noticeable; his work is cited everywhere, from the New York Times to The Atlantic and Sharra Vostral’s 2008 book on the history of menstrual hygiene technology . He has insisted for nearly 40 years that synthetic tampons are dangerous to anyone who listens to them.

And apparently no other leading scientist agrees with it when it comes to tampon fibers and TSS.

Two highly cited studies by Tierno and his New York University colleague Dr. Bruce Hann, conducted in 1989 and 1994, target synthetic fibers, such as polyester foam and rayon, that promote the production of toxins. A 1989 study states that “the greatest stimulation of TSST-1 was observed with polyester and carboxymethyl cellulose” in part because of the high absorbency of the polyester and because carboxymethyl cellulose promotes a gel-like viscosity that enhances the production of toxins. A 1994 study found that tampons made entirely of cotton reduced the risk of TSST-1 in women than viscose rayon tampons or birth control sponges.

“Polyester is a fiber that should never go into the vaginal vault,” Tierno told me over the phone with equal concern and urgency. “It provides ideal chemical conditions that maximize the production of toxins.”

After that phone call, my heart sank. Suddenly, makeup sponges felt like the worst possible item to insert into the vagina. Is the second coming of the Rely tampon stuck in my body?

But four other scientists I called – all of them some of the world’s leading experts on TSS (by the way, they are also white and men) – told me in various diplomatic ways that they thought Tierno’s research on tampon fibers and toxins was suspicious. , and that other scientists have been unable to reproduce or confirm his findings. (Tierno believes they did not attempt to adequately replicate the research.)

In fact, the first scientist I called, Dr. Patrick Schlivert, was not that diplomatic.

He “chases the rainbow,” he said of Tierno. He is “overwhelmingly wrong when he publishes research” about TSS.

Schlivert is sarcastic and eminently self-confident, and I want to roll my eyes at the same time and write down everything he says. He is an S. aureus expert and scientist who – after Todd called toxic shock syndrome – first identified in 1981 the specific strain of Staphylococcus bacteria that caused it. “Not many people know more about S. aureus than Pat Schlivert,” said one scientist I spoke to.

Schlivert says it has long been accepted that the ingress of oxygen into the vagina is the main factor triggering S. aureus to produce the toxin, whether the tampon is made of cotton, rayon, or polyester foam.Even non-Tierno studies have shown an increase in toxin production with the infamous Rely tampons, which, among other things, were made from polyester foam, a key ingredient in many makeup sponges. But Schlivert says a woman with S. aureus present in her vagina during her period will have more than enough bacteria to produce the toxin, no matter what her tampon is made of. “Menstrual blood can help multiply staphylococcus aureus. aureus between 1,000 and 10 billion, ”he said. But for all these bacteria to lead to TSS, “you just need something to activate the toxin.”

This is something, Schlivert said, air.

Every time a woman inserts a tampon or something else, such as a menstrual cup or diaphragm, she runs the risk of introducing oxygen into the normally anaerobic vagina. Typically, Schlivert says, the higher the absorbency and expansion rate of the tampon, the more oxygen is retained. He explained that there are two reasons for this: even before insertion, high absorbency tampons are larger than low absorbency tampons, so the nooks and crannies in the tampon “look like the Grand Canyon” to bacteria; The outer edge of the larger tampons has more contact with the vaginal wall than the smaller tampons. And then, after insertion, the tampons expand even more, causing “immediate expansion and suction of air during insertion.” This is why the high absorbency of the Rely tampon was so important to the outbreak of TSS, he says, and why the CDC recommends using the tampon with the lowest possible absorbency.

Thierno strongly disagrees. He recognizes that oxygen is a factor in determining whether S. aureus will produce TSST-1 toxins, but not necessarily the main factor. He argues that synthetic materials will continue to be the key factor.

“There is no reason for polyester under any circumstances,” Tierno said.

Thug TSS Scholarship Policy

Now I am really confused. These two TSS experts seemed eager to tell the shit about each other to the reporter, and I wasn’t sure which one to trust. Schlivert called Tierno a “record holder” who “cannot keep up with current generally accepted knowledge and publications.” Tierno replied that he had no intention of getting into a “fight” with Schlivert, although when he hears his colleague’s name “it just annoys me,” he said, his Brooklyn accent intensified as his defenses increased. Schlivert “confused many cases with nonsense.” Tierno would not go into the details of the said nonsense, but “let’s just say that there are auxiliary things in the game, and not just science. There is also politics. ” The “politics” of the TSS scientific community turned out to be much more ruthless than I expected.

I needed more scientists to weigh whether polyester foam is a major risk factor for TSS. I independently identified other well-known experts based on how often their names were mentioned in research and news articles about TSS, and learned about three of them. (Dr. James Todd, the Denver physician who first identified the disease, declined to be interviewed.) When it came to whether certain materials increased a woman’s risk of TSS, everyone I spoke to joined Schlivert and Team Oxygen in stating that air is a key factor and the polyester foam itself was a minor factor at best.

Dr. Vincent Fischetti, professor of immunology, virology and microbiology who has worked in the Rockefeller University bacterial pathogenesis and immunology laboratory for decades, was Team Oxygen’s biggest evangelist: there is no better way to capture oxygen for this material. Back in 1989, he co-authored a study on the role of air in the production of TSS toxins , which convinced him that “anything that can deliver oxygen to the vagina can trigger a TSS event,” whether it was made of cotton or rayon or polyester. …

Dr. Michael Osterholm, director of the Center for Infectious Research and Disease Policy at the University of Minnesota and co-author of apair of top three state -of-the-artresearch onTrust and Root Cause of TSS, noted that Trust also contains a surfactant called Pluronic L92, which enhances the production of toxins. But he still told me to trust Schlivert.

“His work has been copied by others and is truly cutting edge,” Osterholm said. He agreed that absorption capacity, as a measure of the amount of oxygen introduced by a product into the vagina and not by the material, is a major factor in determining whether S. aureus will produce TSST-1 toxin. When Rely was taken off the market, tri-state studies found that other high absorbency tampon manufacturers, such as Tampax’s Super Plus and Playtex Super Pluss, still saw an increase in TSS cases associated with their products.

Dr. Jeffrey Parsonnet, an infectious disease physician and professor at the Geisel School of Medicine in Dartmouth, and co-authorof a 1996 study that found Rely had “dramatically increased” TSST-1 production, would not have joined Tierno. on Team Polyester too. “Doctor. Schlivert is usually pretty sure of himself, ”he said with a gentle chuckle,“ but I tend to agree with him. Parsonnet told me that there is “still no decision” as to exactly what chemical composition makes the Rely tampon so dangerous. And he also mentioned Rely’s Pluronic L92 coating, warning us that we don’t know what the makeup sponges are covered with. Therefore, he cannot advise putting anything other than a medical device into the body, but suggested that a makeup sponge during intercourse would be safe for a short period of time.

The three doctors agreed with Schlivert’s theories about Tierno’s theory on a scientific level, but Schlivert also questioned Tierno’s political motives. He criticized Tierno’s involvement in TSS-related lawsuits, even hinting that Tierno was chasing money from plaintiffs who sued the tampon companies, and that he “charged a lot of money for his time [testimony in court] so that he had extra money for his studies. ”Thierno denies this, and in fact claims that many of the leading doctors in the field“ bought locks, supplies, and toppers from tampon companies ”and“ paid for their daughters’ weddings ”with Big Tampon dollars, although he declined to name. These scientists testify “in favor of the tampon manufacturers,” he said. “And I testify on the side of truth.” (For reference, as of 2014, Tierno was the ” Official Medical Consultant ” for feminine hygiene company Veeda, which only sells 100% cotton tampons.)

Schlivert counters that his research on TSS was funded by the National Institutes of Health and not by the tampon manufacturers. But even the same 1996 study that Tierno would agree with, showing that the Rely Super tampon produces more toxins than cotton or rayon, was supported by a grant from Tambrands, Inc., the company that makes Tampax tampons (and since 1997 is a subsidiary of Procter & Gamble, Rely’s parent company).

However, regardless of the alleged motives, all men agreed on one thing: when there is enough S. aureus in the vagina, oxygen can have very, very dangerous effects.

What about makeup sponges?

So if oxygen is a key factor in getting TSS, where are the makeup sponges? Gunther acknowledged the role of oxygen in her blog post and ran an informal experiment.

“I slipped my makeup sponge into a beaker to see how much air could be trapped and was amazed at the amount of gas released,” Gunther wrote. “I did the same experiment with the super plus tampon and saw no bubbles.” (Following the first interview, Gunther declined to participate in this article when fact-checker Lifehacker called last summer, expressing his disapproval that I had not personally followed. Disapproval and hung up.)

Schlivert called Gunther’s informal experiment “useless” and “unscientific”: “The beaker experiment depends on the amount of liquid in the beaker, the size [of the sponge], the total amount of air trapped [in the sponge] (not just the visible bubbles), and too many others.” variables, ”he said. But even if the sponge does trap more air compared to its size, most of the scientists I spoke to said that the risk of a TSS product simply depends on its absorbency. The large super absorbent makeup sponge – like the large super absorbent swab – increases the amount of oxygen in your vagina. Makeup sponges do not advertise their absorbency, but certainly come in different sizes; this may mean that my initial advice to use a larger sponge for more protection may have been unwise.

What about time? It was here that I found perhaps the biggest revelation in all of my research. Conventional wisdom has always held that TSS has to do with lazy use of tampons – leaving it on for too long, or forgetting it and finding it a few days later. spoke to the split when it came to this issue.

Fischetti and Tierno said the risk of TSS is reduced if the tampons are changed within eight hours. But Schlivert and Osterholm said the onset of the disease might have nothing to do with being in a tampon or sponge for too long. In fact, changing tampons frequently and using them one after the other during your period (as opposed to, say, alternating between tampons and pads or blood-absorbing panties like THINX ) can even increase the chances of developing TSS, scientists say: because each insert introduces more oxygen … Parsonne was evasive, but also theorized that consistent “consistent use” of tampons could be a factor.

However, despite the controversy over how long wearing time affects the risk of TSS, Schlivert, Parsonnet, Fischetti, and Osterholm told me that they can safely say that using a makeup sponge every now and then for one hour during sex carries a very low risk of TSS, equal to or possibly less than the risk of regular use of tampons. I breathed a sigh of relief: my track record of quickly removing makeup sponges after menstrual sex was flawless compared to having forgotten to change a tampon for hours.

Thierno objected, saying that I “could fall asleep with [a makeup sponge] given the script. Your job is done. There is a certain art in making love, so sometimes art needs to be expressed. Thus, you cannot immediately remove it. “

In other words, it might seem rude to jump in and go to the bathroom right after sex to pull out a makeup sponge instead of dangling pillows or falling asleep in a lover’s arms. (If you ask me, the male scientist’s paternalistic assumptions about postcoital preferences in adult women did not occur in the context of the scientific survey. There are other physician-recommended reasons for running to the toilet after sex that do not deter us from Ask any woman with a UTI predisposition. However, several doctors and researchers, including Tierno, said that TSST-1 toxin takes several hours to produce S. aureus in high enough concentrations in the vagina to cause TSS. Therefore, it seems logical that removing the makeup sponge within an hour of insertion without successively inserting another sponge later would reduce the already small risk of TSS.

How to assess the risk of TSS

By researching this story, I discovered other ways to determine the risk of TSS – things that would be great to know when books on puberty and boxes of tampons scared me to death when I first started my period. Several doctors I spoke with said that adolescents and young women are much more likely than older women to develop TSS. (The average TSS patient is in his early twenties, Osterholm says, and more than a third of the women who get it are teenagers.)

Schlivert said that of the more than 8,000 cases of TSS S. aureus he consulted on, nearly all were women of Northern European descent, which he said could explain the higher prevalence of the disease in the Upper Midwest, which was inhabited by Scandinavian immigrants. … Tierno also said that “cosmopolitan women” from New York who had more sex partners may be more likely to develop antibodies to TSS than “women from Cedar Rapids, Iowa.” (Was this a reference to the much-publicized TSS case involving Relie in 1982 that Tierno testified against in Cedar Rapids? Or did Tierno cast a subtle shadow over Schlivert, who is a professor at the University of Iowa? We can’t be sure.)

A test for these antibodies exists, but it goes far beyond typical gynecological practice – Schlivert claims that he is the only one who does it. And Tierno thinks the results aren’t worth it anyway; he believes that antibodies can develop over time, so a 15-year-old girl’s test may be useless by the time she turns 20. And he has argued in the past that these findings could possibly be used against TSS patients suing tampon companies. (Unsurprisingly, Schlivert disagrees with Tierno; he believes that unless a woman develops these antibodies by adolescence, she will probably never develop.)

So could any of these doctors directly recommend one of their patients to use a makeup sponge during menstrual sex? This is where they are insured. No one really knows anything about using makeup sponges during menstrual sex. It has not been studied or approved for this use by the FDA. Even the eminently confident Schlivert said that it would take formal and scientific validation to determine exactly how much oxygen a makeup sponge is putting into the vagina.

In other words: can I ask an expert to approve this technique for promiscuous sex during my period? No. Do the world’s four leading TSS experts have any reason to believe that a woman using this method is at a higher risk of contracting the condition than if she had inserted a tampon? Also no.

After all was said and done, deep down I knew that I was going to continue to use makeup sponges during menstrual sex. So I decided to plan for harm reduction because for me the benefits outweighed the potential risks. Using a make-up sponge, despite the negligible likelihood of toxic shock syndrome, has been a cost-benefit analysis of ordering a rare hamburger despite the risk of food poisoning, a disease that is far more likely to occur than TSS.

This is why I find it interesting that the equally low-risk recommendation that has generated an astonishing level of vitriol online was simply about the vagina. Some of the comments seemed to be based on sanctimonious morality: “Fuck, wait,” until you run out of periods, Michael suggested on Facebook . “Nobody has the right to have sex on demand.” Others smelled like good old sexism: “I’m not a woman, and even I can say this is terrible, terrible advice!” – observed a person who is physically unable to follow this advice.

In all fairness, this overreaction was probably also related to a lack of information about how rare the disease is, what causes it, and how much of the vaginal population is immune. I started this random odyssey with almost nothing about the science of TSS, and came out on the other side with a much better understanding of this apparently complex disease. Here’s what we now know:

- TSS occurs when the bacterium Staphylococcus aureus produces high concentrations of TSST-1 toxin in the vagina and successfully enters the bloodstream. The pH of the menstrual blood causes Staphylococcus aureus levels to skyrocket.

- TSS is rare. Last year, the CDC only reported 24 cases of TSS associated with staphylococcus aureus. At least 80 percent of the population is immune because they developed antibodies to TSST-1 by adolescence.

- Studies have shown that TSS is more common in adolescents and women between the ages of 20 and 30.

- Thierno suggests that women who have more intercourse or live in densely populated areas are more likely to have antibodies to protect against TSS. (Schlivert, for the record, disagree.)

- Microbiologists agree that oxygen in the vagina is needed to trigger the production of TSST-1 toxin, which is why tampons are associated with TSS.

- It is still unclear if the type of material or fibers of tampons or anything else inserted into the vagina affects TSST-1 toxin. Some leading experts believe this is at best irrelevant to TSS at all, and at worst a secondary factor. One leading expert I spoke with believes that this is the main factor causing TSS.

- Regardless of the material, higher absorbency tampons have long been associated with TSS, probably because their size and degree of expansion allow more oxygen to enter the vagina.

- After oxygen enters the vagina, the toxin is produced over a period of several hours.

- While no doctor or microbiologist I spoke to would promote the use of an off-label makeup sponge during menstrual sex, most agreed that the risk of TSS with them is at least as low. as with using tampons – possibly below. since the sponge is likely to stay in the vagina for less time.

“I don’t think we teach people how to look at their own risk-benefit ratio, and I think the scary story will slip away very easily,” Gunther noted in a recent article on TSS in The Cut . I agree, so let’s take a look at my ratio: I’m a 34-year-old, pretty messy New Yorker who obviously has a short vaginal canal as I’ve never had a problem finding a makeup sponge after sex and catching one. … My risk of TSS is low. I have continued to use this method of intermittent sex ever since I started researching this article in the summer of 2017.

But I definitely applied what I learned to lower my risk. I took out the sponge for an hour after injection to prevent toxins from forming. I only use one small sponge at a time, for only one sex session at a time, to reduce the amount of oxygen entering the vagina. (And for the same reason, I alternated between panties for an absorbent period and tampons for my period.)

Sea sponges seem to be more dangerous than makeup sponges – even more laissez-faire Schliver advises against using them for allergy-related reasons, and according to some reports, they are more likely to break – so I avoided using them. Several Lifehacker commenters have endorsed menstrual discs, a vaginal device specifically designed to collect menstrual blood, as an alternative to menstrual sex. This was intriguing to me until I read a recent study that found that menstrual cups may be even more associated with TSS than tampons. Menstrual discs are not the same as menstrual cups, but they capture blood in a similar way. (Schlivert, of course, remains loyal to Team Oxygen: he believes these results are likely due to the fact that menstrual cups inject more air into the vaginal canal than tampons.)

All these precautions aside, some women may not be worth the risk of using a makeup sponge. But for me, the risk of contracting TSS, which is a tiny fraction of the risk of dying in a car accident , is worth the occasional bloodless sex. I would really like to be aware of the risks and science behind TSS ahead of time so that I don’t have to spend my entire sex life worrying about it.

So, here’s what I propose: teach girls the scientific details of TSS in health and sex education classes – its minimal risk, high levels of immunity in women, how long it takes to develop its toxins, and what exactly is believed to be the cause. tampon companies to publish the same information in inserts in their packaging and on their websites. And above all, put more money and effort into demystifying women’s sexual health. This means, of course, educating them about their diseases, but it also means taking their gender-related issues seriously.

Bleeding for a week every month is weird, uncomfortable, and sometimes painful. The least we can do is not subject millions of women to frightening misinformation about the terminal illness, and then subject them to harsh condemnation when they suggest ideas for how to improve the “art of lovemaking” – for example, a relatively low risk (albeit off-label) a way to fuck during your period without bloodying your sheets.

This article was edited by Melissa Kirsch with assistance from Alice Bradley and Beth Skorecki and fact-tested by Jessica Corbett.